Some judges in the EU can no longer trust their own governments to protect the rule of law in their own countries. Judges in the EU are also EU citizens and as such entitled to the same freedom, security, justice and fundamental rights just like any other EU citizen. Yet this also is no longer the case in every country of the EU. In Poland judges are suspended and then persecuted. There is work to do now for all of us to support the battle of the Polish judges for the preservation of their independence and impartiality. This is a responsibility for the whole EU judiciary as a vital institution of the EU.

The European Union is and should stay an area of freedom, security and justice with respect for fundamental rights and the different legal systems and traditions of the Member States (article 67 EU Treaty). This may now be even more important than the economic freedoms the EU also stands for.

Not so long ago the position of judges in the EU was safe, secure and protected. It was usually sufficient to observe that this position was endangered to rectify the situation. This however has changed very fast during the last decade. Particularly in Poland, but also in Hungary and some other EU countries, things are changing quickly and in a very wrong direction.

Some judges in the EU can no longer trust their own governments to protect the rule of law in their own countries. There can be no misunderstanding here. Judges not only live in the EU, but they are obliged to apply EU Law every day and are vital for securing the freedom security, justice and fundamental rights for every single EU citizen and organisation.

Judges in the EU are also EU citizens and as such entitled to the same freedom, security, justice and fundamental rights just like any other EU citizen.

Yet this also is no longer the case in every country of EU. In Poland judges are suspended and then persecuted. Their income is cut and they are being disciplined at will by the government of the Republic of Poland based on national legislation, which is at variance with the core of EU law and a direct violation of the rule of law. this is clearly recognized in the ruling of CJEU C791/19R of 8 April 2020 holding provisional measures ordering the State of Poland to suspend the work of the Disciplinary Chambers in Poland immediately.1

Neither the EU Commission nor the State of Poland have paid any effective heed to this ruling. From the State of Poland that might perhaps have been expected. But as an ordinary Dutch judge I am deeply disturbed by the lack of activity of the EU commission and the EU Council in trying to force the EU Member State of Poland to observe this CJEU ruling at once.

Judges in the EU are not only one of the three powers of the trias politica in their own countries. Together they are a body of EU judges and thus one of the three powers of the trias politica within the entity of the EU as a whole. They are as such the EU judiciary. This EU judiciary is a vital institution of the EU.

It is the task of the other members of this EU trias politica (the EU Commission, the EU Council, the EU Parliament as well as governments and parliaments of Member States) to protect the independence of the EU judiciary and keep the balance within this EU trias politica.

So far the EU Council and EU Parliament have taken some interesting steps in securing a new rule of law instrument, but this will only be fully effective in about two years. Knowing how fast the changes in Poland are now taking place and what is actually happening to Polish EU judges, this is way too slow.

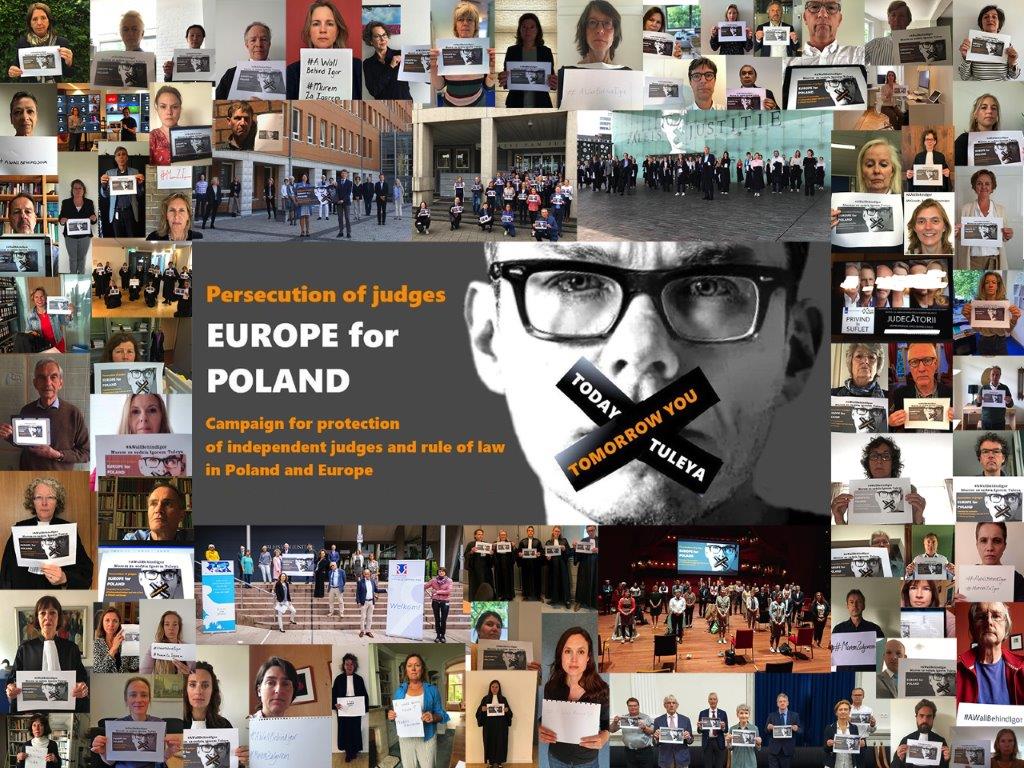

The cases of Polish judges like Igor Tuleya, Beata Morawiec and Pawel Juszczyszyn show clearly what may happen in any other EU country to any other EU judge if the EU Commission, the EU Council, the EU Parliament and governments and parliaments of EU Member States do not step up their pace quickly in securing the rule of law and in protecting the independence and impartiality of the EU judiciary as a whole. The EU Commission cannot wait any longer and needs to start with the execution of the activities 1 till 4 as mentioned in the article of Dariusz Mazur.2

In my opinion these developments also make it necessary for judges from all EU states to support each other, come out of their dignified and silent position and take a firm stand in the spotlight in the front of the EU stage. They need to be seen and heard as necessary and vital for the survival of the values on which the EU is build.

If other strongholds of the EU trias politica fall short of securing this position of the EU judiciary as a vital institution, it is a duty for this body of EU judges itself to show publicly to the EU audience (governments and institutions alike) that the EU judiciary is not asking for respect and protection for its own sake, but for all EU citizens. EU judges should be enabled to protect the freedom, security, justice and fundamental rights of EU citizens and organisations, as this is their duty.

How to achieve this is quite another matter. This situation has not arisen before. As the report Justice under Pressure 2015-2019 shows Polish judges and their organisations have been battling on for the rule of law in Poland, but within the EU itself this battle was not picked up on a large scale.3

Two Dutch exceptions to this observation must be named here. Frans Timmermans, vice president of the former EU Commission with among other things rule of law and human rights in his portfolio, battled hard for the maintenance of the rule of law in Poland. Too hard in the eyes of some, so now he is Vice President of the current EU Commission with a portfolio where he has no longer any responsibility for the rule of law in the EU. Kees Sterk (as a Member of the Dutch National Council of the judiciary) was president of the European Network of Councils for the Judiciary (ENCJ) until July 2020. Under his presidency the Polish National Council of the Judiciary was suspended as a Member of ENCJ. There is still a possibility to expel the NEO Polish Council of the Judiciary altogether from ENCJ.4

It is now up to the successors of Timmermans and Sterk to hold steadfast to this course.

Not a moment too early on 6 November 2020 the Consultative body of European judges (CCJE) came with its Opinion number 23 on the role of associations of judges in supporting judicial independence, creating a framework for the body of EU judges/EU judiciary to organise on national and EU level.5

Different national organisations of judges can work together within or outside the several European judicial organisations. In my view this is necessary to create awareness of the position that the EU judiciary finds itself in, a very good way to advocate the common values of the independence and impartiality of the EU judiciary as well as indispensable to act to protect the freedom and the fundamental rights of EU citizens and organisations if this judicial independence and impartiality is threatened.

As John Morijn shows in this issue of NJB,6 the threat is real that within years from now Poland and perhaps some other EU countries will no longer have an independent and impartial Judiciary that corresponds to EU standards.

To me as a Dutch judge as well as an EU judge this would mean I could then no longer do my own work properly. It would mean I can no longer trust the decisions of my colleague EU judges from Poland for instance at face value. As a judge I would no longer be able to guarantee that in my decisions EU standards are the same as in the whole of EU. Until now I can consult all the decisions of my colleague EU judges on the interpretation of EU laws, which have become enshrined in Dutch national law and in the law of all other EU countries. After that I can and preferably must decide the same way as for instance a Polish colleague has done, if the same legal question arises.

That may be legal questions in cases touching the daily life of Dutch citizens on for instance consumer law, family law, investment law, transport law, social security law or housing law. Once independence and impartiality in Poland are gone, I will no longer be sure that the decisions of Polish EU judges are only based on EU laws and have not been unduly influenced by the interests of the Polish government and/ or its reigning political parties. As a Dutch judge and an EU judge I would possibly be torn in two and could be forced to decide not to follow a judgement of my Polish EU colleagues and to explain in my decision why I can and will not answer the legal question put to me in the same way my Polish EU colleagues have already done.

As a Dutch judge and an EU judge at the same time, I do not want to get in this position. It is not the job of a judge. My independence and impartiality that are necessary to protect and secure the rights of Dutch citizens might then also be in danger.

This is why in my opinion freedom, security and justice with respect for fundamental rights and the different legal systems and traditions of the EU are more important than the economic freedoms that the EU also stands for. Only when the independence and impartiality of the EU Judiciary as a whole is upheld, citizens and organisations of EU may thrive economically. When the independence of the judiciary of one member country of the EU is no longer guaranteed, the independence and the impartiality of the whole EU judiciary is at stake and urgently needs protection. That is why I think it is high time that EU judges close their ranks and must stand shoulder to shoulder in solidarity with the Polish judges now.

Just as Dariusz Mazur did in his article, I have made a list of what is needed now, in my view.

1) Much more awareness of this urgent, serious and fundamental problem by all ordinary EU judges and EU institutions. The march of the thousand robes, organised by the Polish organisations of judges on 11 January 2020 was a unique first sign of public solidarity between EU judges. There were delegations of many EU countries, some of them not larger than one or two judges.

It still makes me proud that the largest delegation came from the Netherlands. I felt very uneasy and sad to put on my robe and walk as a protester on Polish soil. It was necessary and I never thought that I, as a judge, would feel urged to act in this manner.7

This march was not enough to stop the Polish government infringing the independence of the Polish judiciary and worse it did not energise the EU institutions to any effective action.

The solidarity between EU judges has grown since then. In December 2020, again at the initiative of Polish organisations of judges, more than 5000 signed letters of EU magistrates (about 1000 Dutch) to support the rule of law in Poland were delivered to the EU Commission.8 This is an enormous number of signed letters but seemingly not enough to be of any real interest to the EU Commission, judging from the fact that the EU Commission saw no need to delegate one of its Members to receive these signed letters publicly in person.

2) Much more advocacy of the importance of the rule of law, the independence and impartiality of the EU judiciary.

As shown by the examples mentioned before, the EU judiciary is vital for the EU to justify its existence as an economic union performing its duties in the promotion of the welfare and wellbeing of EU citizens and organisations.

Until now the EU institutions and some Member States have been very slack in recognising this. To a large extend it is up to them and to civil society to recognise and make clear that once you have lost the independence of the EU judiciary as a vital part of the EU trias politica, the EU as a whole will no longer be a democratic entity under the rule of law. I really do not understand why this risk seems to be so underestimated.

The last letter of four international European organisations of magistrates to Charles Michel, President of the EU Council, from 23 November 20209 has not received an answer that contains any real concern or involvement. It is a little bright spot that the Dutch government has decided to support the EU Commission as an EU Member State in the Case C-791/19. It is also a good thing that Dutch parliament has come to recognise the danger to the rule of law in the EU. On 10 December 2020 the standing Commission of Justice and Security of the Second Chamber has devoted a hearing to the subject of the situation of the rule of law in the EU and Poland.10

3) Actions to support of the rule of law, the independence and impartiality of the EU judiciary and in Poland. That actions can arise from informal and formal cooperation between organizations of EU judges is proven by the efforts trying to prevent the lifting of the immunity of Polish judge Igor Tuleya.11

That this action did eventually not succeed, because on 18 November 2020 the immunity of judge Tuleya was lifted by the Disciplinary Chamber of the Supreme Court in Warsaw, should not deter the EU judiciary from further actions to show active solidarity. They were a real start of an effort to coordinate the support the Polish judges in a more structural way throughout the whole EU judiciary and this decision is clearly and directly contrary to the Court of Justice’s Order from 8 April 2020 in case C-719/19 R. A strong action could be to form a standing EU support group for Polish organisations of judges and magistrates, like Iustitia, Themis and Lex Super Omnia. Its purpose should be a more strategic and long-term approach to resist the attacks on the independence of the Polish judiciary and with that the attacks on the EU judiciary as a whole. Members of this group would obviously have to be members of all these Polish organisations, because they are demanding help and solidarity and so they should be in the lead.

Members must also come from European organisations representing national organisations of magistrates, like EAJ, MEDEL and AEJA, to help the Polish organisations of judges to be heard and to support them throughout the whole EU.

Representatives of several national organisations of magistrates of EU Member States must be added to keep the lines short between daily working EU magistrates and the higher officials from the European judicial organisations. These could be members of national organizations of judges, preferable from other Middle European countries like the Czech Republic, Hungary or Bulgaria. They are facing similar problems as the Polish judiciary.

It would be wonderful if the Netherlands as an EU Member State could somehow support and host this standing support group as a clear sign of support of the rule of law and the independence of the EU judiciary in EU.

A first example of what this support group may do, is the promotion of the distribution in Europe of a version of the Polish film about the March of the 1000 Robes, released recently in Poland.12

That would be a striking way to raise awareness of the problem inside and outside the EU judiciary.

Another example could be to start the documentation of cases of Polish magistrates that are being prosecuted by the Disciplinary Courts in English and/or French. That would enable the EU institutions and EU citizens to follow these cases closely and critically.

A third example of what may be done is to start a crowdfunding action under EU magistrates to realise a fund to support these judges financially the next two years. This is perhaps a daring thought, but it would be real and immediate support of some brave Polish judges, like Pawel Juszczyszyn, Beata Morawiec and Igor Tuleya, who are today paying the price for their actions – all too literally – by having their salaries cut after the lifting of their immunity.

Dreaming of an ideal world is necessary for a better world. Nevertheless there is work to do now for all of us to support the battle of the Polish judges for the preservation of their independence and impartiality. In my view this is a responsibility for the whole EU judiciary as a vital institution of the EU.